Visit to the Italian front | Photo provided by the Unamuno House Museum in Salamanca

Childhood and youth: 1880-1911

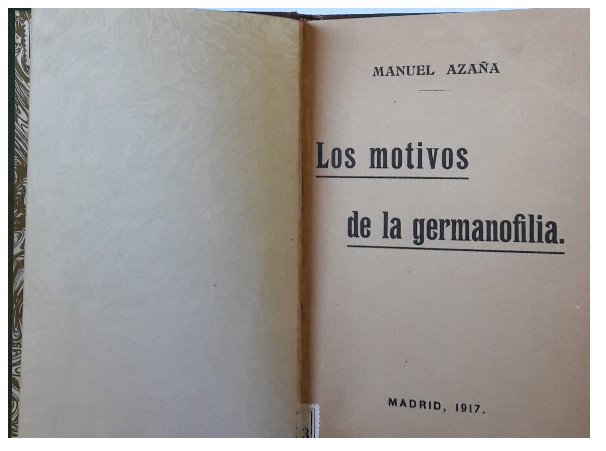

The reasons for germanophilia. Madrid, Imprenta Helénica, 1917 CP Enrique Moral Sandoval | Colección privada de Enrique Moral Sandoval

Photo with Rafael Altamira and Américo Castro in Reims. Group of men watching the consequences of the bombings in Verdun. | Photo provided by the Ateneo de Madrid

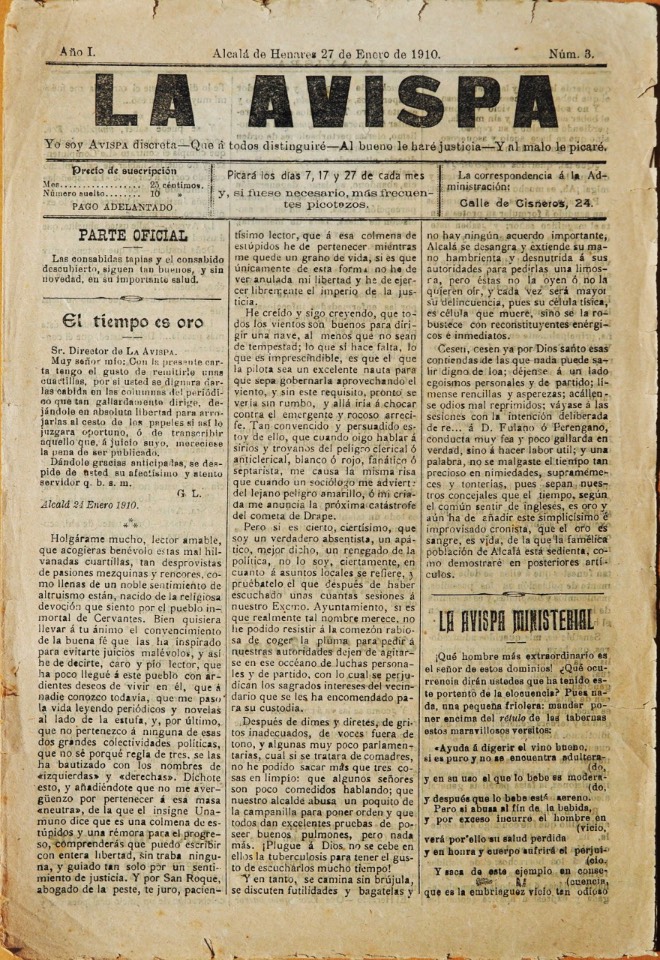

La Avispa | Private Collection of Julio and José María San Luciano

Manuel Azaña Díaz was born in the street Image of Alcalá de Henares on January 10, 1880, in the heart of a family with a long Alcalaín tradition. His father, Esteban Azaña Catarineu, was mayor of Alcalá when the statue of Cervantes was erected and is the author of the History of the city of Alcalá de Henares. His mother, Josefa Díaz-Gallo Muguruza, died in 1889 and, shortly afterwards, his grandfather Gregorio. The following year, his father also died. Manuel and his brothers: Gregorio, Carlos, who will die very young, and Josefa, remained in the care of their grandmother, Concepción Catarineu.

He studied secondary school in Alcalá, at the Complutense San Justo y Pastor school and in 1893 entered the Agustinos de El Escorial. In 1898 he graduated in Law at the University of Zaragoza and, two years later, he presented his doctoral thesis The Responsibility of the Multitudes at the University of Madrid.

With a group of friends he founded the magazine Brisas del Henares in his hometown, and collaborates in Gente Vieja. In both with the pseudonym of Salvador Rodrigo.

He works as an intern in a law firm in Madrid, which he abandons to return to Alcalá to manage his family’s assets. He manages the family lands, a roof, a soap factory and creates, together with his brother Gregorio, an electricity company. She founded the magazine La Avispa, dedicated to municipal criticism.

In 1910 he joined as an official in the General Directorate of Registries and Notaries and on February 4, 1911, at the inauguration of the House of the People of Alcalá de Henares, he gave his first political conference The Spanish Problem.

Words of Azaña

About your childhood.

I loved my books, and the room in which I read, and its light, its smell. I loved the house, so fearful in the evening, haunted by the shadows of the dead, filled in my opinion with the echo of certain voices forever extinguished.

[…]

The novels of Verne, of Reid, of Cooper, devoured in the melancholic solitude of a village house overshadowed by so many deaths, aroused in me a thirst for furious adventures. He loved the sea passionately. I dreamed of a wandering life […] What happened to the children of today with cinema happened to me: they want to be Fantomas as I wanted to be Captain Nemo […]. I devoured with a manifest ravage of my inner peace how many books of imagination I found stored in my grandfather's bookstore: Scott, Dumas, Sue, Chateaubriand, something of Hugo, translated, and his Spanish henchmen. I remember living then in a prodigious world. From that test, which helped me to understand the madness of Don Quixote, my early hobby was dazzled to read everything.

The garden of the friars. 1927.

About the teaching received

… it is not studied to know, but to approve, and it is not taught to run and it is not sought to form intelligence but to force the boys to recite ludicrous choir manuals, full of follies […]

In general, the boys in Spain are not taught anything that can go against religious prejudice, or against certain institutions; for this they have no scruples in blatantly missing the truth, or in presenting the works, works and discoveries of the enemies […] villainously adulterated.

[The current education]… is not aimed at forming character, putting its center of gravity in one’s own conscience, indoctrinating men into the eternal powers of self-respect, personal dignity and respect for others, but it is based entirely on religious dogmatism, from which it turns out that when faith is lost, the reasons that previously had to be honored and complete also disappear for the majority of men.

The Spanish problem. Lecture delivered at the Casa del Pueblo. Alcalá de Henares, February 4, 1911.

About the power of education:

The men of my generation […] do not want nor can we lose hope in the future […]. Hence our intention to […] persuade our fellow citizens that there is a homeland to redeem and redo for culture; for justice and for freedom.

Because of the culture I have said and if you meditate well you will understand that I have said everything.

[…]

This task, which is the longest, is the decisive one: "Give me the university," said Renan, "and I'll leave everything else to you."

The Spanish problem. Lecture delivered at the Casa del Pueblo. Alcalá de Henares, February 4, 1911.

About the Story:

In Spain […] there is a nucleus of people, increasingly smaller, who oppose by system the introduction into our soil of all novelty, and who abhor, in terms of ideas, what the foreign marchamo brings.

Searching in the past for reasons of enmity and interpreting History to make it serve as food for hatred is an aberration […] we have the right to look back without pride and without melancholy, to mock our mistakes and take an example of the virtues, of value, of perseverance, where they exist, and to draw from some and other lessons for the future.

The reasons for germanophilia. Lecture delivered at the Athenaeum. Madrid, May 25, 1917.

About democracy:

Will Spain be able to join the general trend of European civilisation? […] What needs to be done, what means will have to be used for this transformation to be verified? […] The only medium […] is instruction, a well-oriented teaching and firmly given from school to university […]

Essentially the democratic organization demands: A body of voters; a body of representatives that they elect; a small number of men of government drawn from among those who represent the opinion of the majority […] That body of voters is the natural and indispensable foundation of the regime, because how will there be government of the people by the people if there is no people?

[…] Neither the people nor anyone should be given pieces of bread, as well as alms, but organize society on a fair basis that allows that piece of bread to be earned by the people themselves […]

Democracy have we said? Well, democracy.

The Spanish problem. Lecture delivered at the Casa del Pueblo. Alcalá de Henares, February 4, 1911.