Azaña at the Goya Theatre with Margarita Xirgu after the performance (Published in Nuevo Mundo, 25 December 1931). | General Archives of Administration

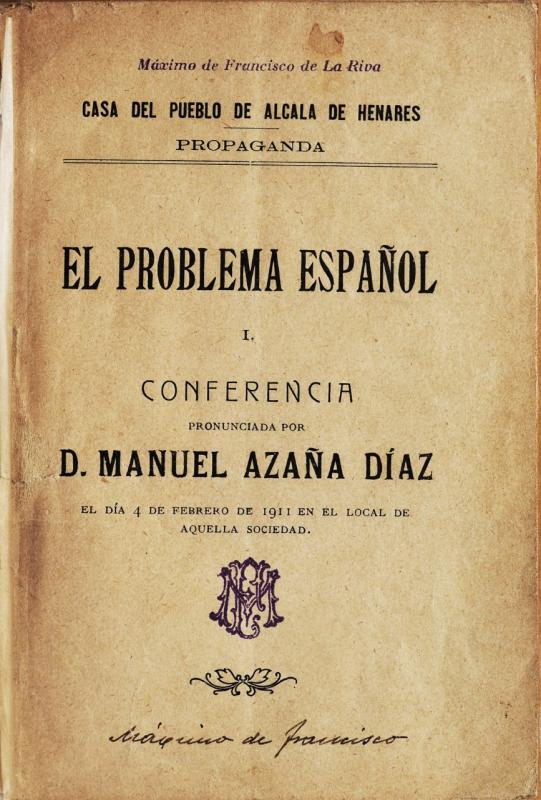

Intellectual in the Silver Age of Spanish culture: 1911-1931

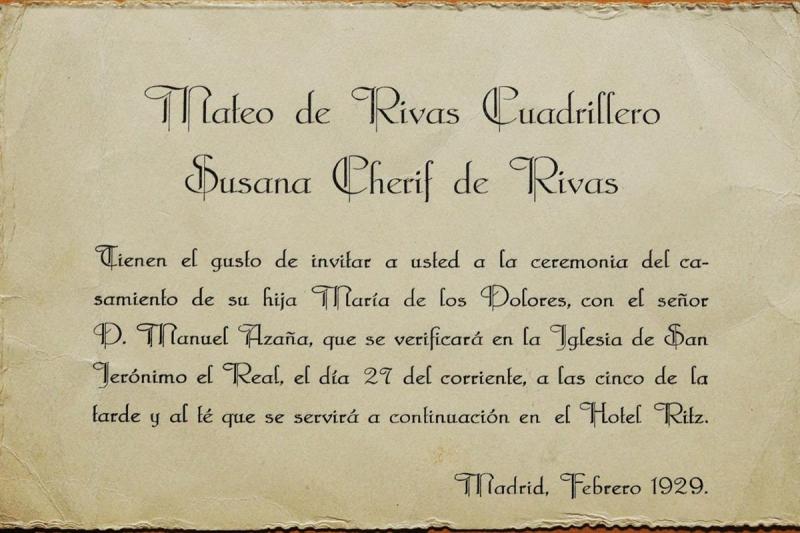

Invitation to the wedding of Manuel Azaña with Dolores de Rivas Cherif, held on February 27, 1929 at the Church of the Jerónimos in Madrid. | Private collection of Julio and José María San Luciano.

Azaña and Lola. Estampa Magazine. Photo Azaña y Lola (cover of Estampa magazine, September 17, 1932) | National Library of Spain

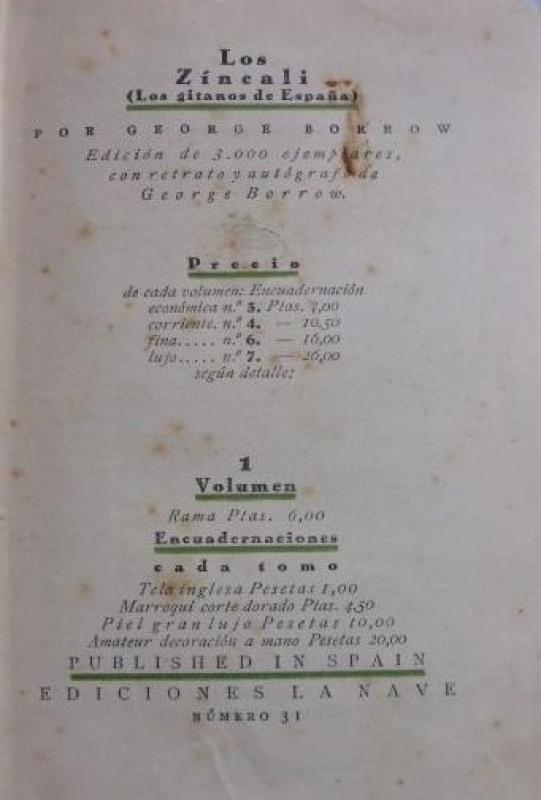

George Borrow, Los Zincali (Gypsies of Spain). Translation of Manuel Azaña. Madrid, Ediciones La Nave, 1932-CPMS | Private collection by Enrique Moral Sandoval.

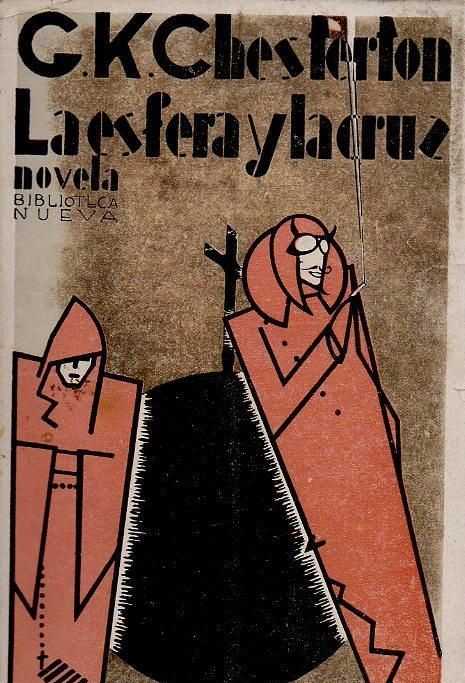

G. K. Chesterton, The Sphere and the Cross. Translated from English by Manuel Azaña. Madrid, Biblioteca Nueva, 1 930. CPMS | Private Collection of Enrique Moral Sandoval

The Spanish-Alcalá de Henares Problem, Casa del Pueblo de Alcalá de Henares, 1911 | Julio and José María San Luciano Paticular Collection

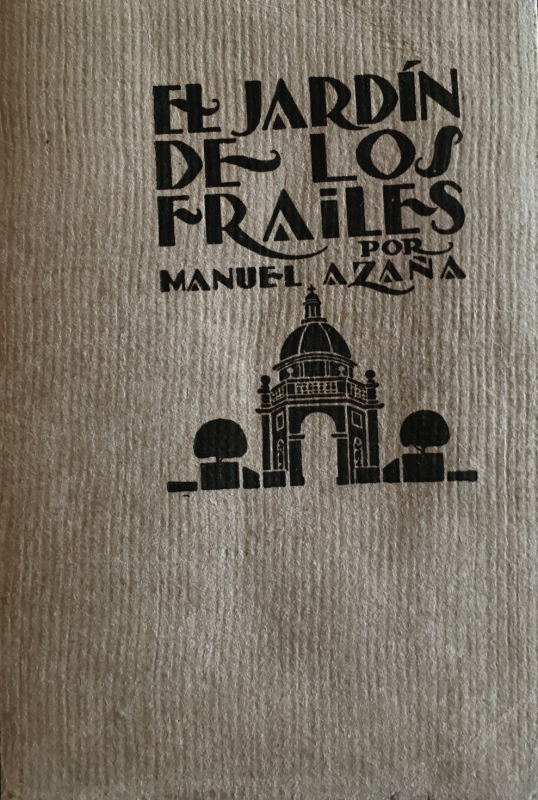

The garden of the friars. Madrid, CIAP, 1927. With handwritten dedication to José María Vicario). | Private collection by María José Navarro.

Between November 1911 and October 1912 he remained in Paris. He joined the Reformist Party and, in February 1913, became secretary of the Ateneo de Madrid, a position he held until 1920. Sign the manifesto of the Spanish Political Education League.

During the First World War, Azaña is a staunch defender of the Allied cause. Visit the war front on three occasions. He publishes his first book Studies of Contemporary French Politics. The military policy (1919).

At the end of 1919 he traveled to Paris, together with his good friend Cipriano de Rivas. Upon their return, they founded The Feather together. In 1923 he directed the magazine España.

His candidacy for a deputy for Puente del Arzobispo failed in 1918 and 1923, after the coup d’état of September 1923 he declared his rejection of the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera and in 1924 he wrote Appeal to the Republic, in which he declared the monarchy incompatible with true liberalism, which is essentially democratic, and participated in the creation of Acción Republicana in 1925.

In 1926 he received the National Prize of Literature for his Life from don Juan Valera. In 1927 appears The Garden of the Friars. During this period, Azaña, who is fluent in French and English, translates numerous works (Borrow’s Bible in Spain, Voltaire’s Memoirs, Chesterton’s Sphere and Cross or Cendrars’ Black Anthology).

In 1929 he married Dolores de Rivas Cherif, sister of Cipriano.

In June 1930 he was elected president of the Ateneo de Madrid. He publishes his play La corona, which will be premiered in December 1931 in Barcelona, already with Azaña becoming president of the Government.

Words of Azaña

Democracy and Republic:

In essence, there are two methods of governing a people: irresponsible absolutism, the true "Old Regime", that is, the one that preceded the French Revolution in continental Europe, and liberalism organized in democracy, by the establishment of which has been fought in Spain for more than a century, without achieving its complete triumph.

Our salvation calls for a regime that is in keeping with the human meaning of life: liberalism and the guarantees of democracy.

Liberalism claims for the existence of democracy […] Democracy means that free men defend, exercise, guarantee for themselves their own freedom. And if they don’t, they are not free, even if they are liberal.

If the person who is given the vote is not given the school, he suffers a scam. Democracy is fundamentally a reviver of culture.

These are the hallmarks of our policy: universal suffrage, Parliament, free press.

Manuel Azaña, Appeal to the Republic, 1924.

We oppose the alleged tactical assent to this main statement: we are Republicans. We maintain that the establishment of the Republic in Spain will not only satisfy the designs of pure democracy, but will also open the way, today closed by historical powers, to the just, reasonable, human government, which complies with the free peoples.

We affirm that in Spain the political problem first consists of moving institutions.

The Republic will also allow us to live better with the democracies of the world.

Manifesto of Republican Action. Madrid, May 1925.

We all belong in the Republic, nobody is banned by their ideas; but the Republic will be republican, that is, conceived and governed by the republicans, new or old, who all admit the doctrine that the State bases on freedom of conscience, on equality before the law, on free discussion, on the predominance of the will of the majority, freely expressed. The Republic will be democratic, or it will not be.

We come to meet the country, not as sterile agitators, but as rulers; not to subvert order, but to restore it […] We are aware of our responsibility and the difficulties that await us and we are determined to face them, without sparing any sacrifice.

We cannot finish off these statements by concluding to them the promise of an era of happiness, of ventura and of greatness. Freedom does not make men happy; it makes them simply men.

The revolution in progress. Address at the Republican rally of the Plaza de Toros. Madrid, September 28, 1930.

About female suffrage:

It is a special argument that women are unprepared for political issues.

The same could be said of men […] What we say is that there is no reason to treat the two sexes unequally in this very simple function of voting […] Everyone who votes, man or woman, knows very well what they want, and the meaning of their vote […] And it is an injustice to argue with the conservative inclination of the female sex, which would jeopardize freedom […] although universal female suffrage would be a reinforcement of conservatism, that would not be a rational reason to deny them their right […]. The trick would be for the women to defend tomorrow what the men have let lose.

Mrs. Fulana de tal Vote! Spain, March 22, 1924